Energy is all around us, but are invisible sparks contained within letters? Words? Might this be a bit too extreme? Well, for those Jews who are spiritually inclined, the answer is absolutely yes! The Hebrew language is called Lashon HaKodesh / a Holy Language for many reasons, but one of them is the belief that a name is not just a random name, and a word does not exist by happenstance—it’s not just a word. Letters are things1 with a potent energy that enables a word to be, it gives a word existence. This is hard to comprehend.

For example, in English, the roots of words may make not sense at all. For example, what is the relationship between the word ‘air’ inside of the word ‘chair’? Or the word hair? Or the word ‘ear’ contained within the word ‘bear’? Is there possibly any connection? We could go on and on.

But in Hebrew, the root word always makes sense. It is the essence of the word and expands understanding of its very nature.

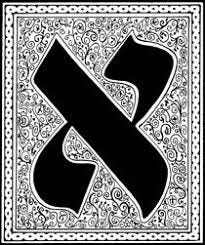

Our Jewish mystical tradition teaches that the Hebrew alphabet has divine origins and is no less than the building blocks of creation. In B’reisheet / Genesis, we learn that the entire Hebrew Alphabet, Aleph to Tov, was created even before anything else2! The words that follow it explain what exactly The Eternal is bringing into being.

In Hebrew, there are an infinite number of opportunities to dive deep into a single word, let alone a phrase. You can play games with each word: by finding its opposite meaning hiding right there within the word, by discovering root words within words that deepen its meaning, by forming new associations and meanings based on a letter’s placement, and locating thematic allusions by sourcing where in the Torah the word first appears.

Yet all that amounts to a drip of water in an ocean. There is so much more, much, much more. But now, we’ll just examine one tiny speck of a drip…by going on a spiritual journey with Hebrew as our guide, focusing on Passover (Pesach). With this lens and an open mind, we’ll discover insights.

In Hebrew, Peh-Sach /Pesach means ‘the mouth discusses/ tells’. Hmmm, interesting, no? This is actually what we do on the holiday. We eat, we talk, we share a story. This goes further though. According to Kabbalistic teachings, our redemption from Egypt refers to our freedom not only from slavery, but from our ability to speak in a certain way. They posit that the entire story of Egypt began with the improper use of language.

As Rabbi Mel Gottlieb relates, our sages said our experience of slavery in Egypt became reality because of evil speech and gossip / lashon hara brought about by Joseph’s interactions with his brothers and his subsequent exile to Egypt. As a youth, Joseph retells his dream in a way that threatens his brothers, then his brothers scheme against him, arranging for his demise. They then lie to their father, and don’t own up to their grievous sin until years later. But Joseph is culpable also. Joseph interprets his dream of greatness to his brothers, but later, in Egypt, gains a sense of humility. He attributes his unique ability to interpret dreams to Hashem. Later, when interpreting the dreams of Pharaoh, despite being in the midst of an idol-worshipping, death revering culture, he makes his heritage known.

“So the spiritual task of Pesach is the purification of speech through telling. It is this holy work that leads us from slavery to freedom." ~Rabbi Mel Gottlieb

So, now we know that Pesach / Peh - sach ( peh-samech- chet), actually means the mouth speaks, it makes sense that the recounting of our story is from a special book called the Haggadah (the telling) which we read at the Seder3. During the Seder, we are transported to that time and re-experience it; by tasting, by eating, by telling. It is no coincidence that Pharaoh (peh - rah (peh-resh-ayin-hei) / literally, evil mouth) is the ruler of Egypt which in Hebrew is called Mitzrayim, a place of constriction. Slavery begins with the limits of free speech, and of speech that is full of pride.

But there is more in the Pesach story about speech. Moses has a spiritual encounter with The Eternal at the burning bush. He is appointed to bring his people out from Egypt but responds saying that he is ‘heavy of speech’ (Exodus 4:10)4 and therefore cannot be the messenger to bring his people out. Some commentators say that this phrasing alludes to a speech impediment. But this is a simple explanation of a something much more complicated and deep.

Rabbi Akiva Tatz teaches that the difficulty for Moses was an inability to bring down and communicate incredibly spiritual and lofty ideas. Moses felt he was unable to be the effective transmitter of such holy communication at this stage. But we know that by the time we are in the wilderness, Moses gains his faculty of speech and communicates with The One ‘face-to-face’ and goes on to give detailed instructions all throughout the rest of the Torah, culminating in his eloquent discourses in Devarim / Deuteronomy (ironically in Hebrew called ‘words’, see below).

On Passover, we are not to eat Chameitz (fermented grains, those that have risen). The spiritual meaning is that we stay away from food that is ‘puffed up’, akin to having an inflated sense of ego. We are what we eat. So, we eat only Matzah (bread that is unleavened, not inflated). But in examining the spelling for both, there is only one letter that is different between Chameitz (chet - mem - tov- tzadee) and Matzah (mem-tov-tzadee-hei). Chameitz begins with the letter Chet 5 (a visually closed letter, ח) versus Matzah which ends in Hei (an open letter, ה). When you put these letters together, they form a journey from being closed to open!

The letter chet is self-contained, all within itself, while the shape of the letter hei is open, space flows in and out. There is an exchange, an openness to new ideas, new ways of thinking. The letter hei is also symbolic of Hashem, since it is evocative of the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter name for The One: (yud-hei-vov-hei). Two of the letters are hei.

How do we relive this redemption of our speech? We relive our history, and commemorate it with a retelling of the story. Yet, Moses’ name is absent from the entire book. Perhaps bringing Moses into this retelling loses the focus. It was our speech to the One that prompted our redemption. Only after we cried out to Hashem was our suffering noted. We needed to call out, to cry for help, in order to be saved. We needed to recognize a higher power6

The days leading up to Pesach we eat chameitz, which is where we were before the redemption. We then retell the story of being in Egypt, of being closed and constricted when we had only ourselves to fall back on. In the midst of evil, according to the Torah, it took years for us to realize that we needed to cry out. To admit that we are not alone. We needed to shed our egos, and partake of the matzah. Passover calls us to be open…open to all who want to join in, open to a judgment-free zone where all types of Jews are accepted7 and all questions are encouraged. It’s an expansive place to be.

even ‘thing’ in Hebrew, davar, also means word! It forms the root word for the book of Deuteronomy, in Hebrew called Devarim.

The source for this is the Hebrew wording in Genesis 1:1. בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ The bolded word is “Et” Aleph + Tov. This word is often a direct object and therefore not translated in the English { when God began to create….}. There is no punctuation in the Torah, so the mystical tradition is that the Hebrew alphabet was created first in order to provide an essence to everything that followed.

Seder means Order, as there is a special order to the Seder.

The Hebrew word khevad / chaf - vet - daled is usually translated as slow of mouth, slow of tongue, but the root word means heavy or burdensome.

The letter chet is an actual word in Hebrew meaning ‘missing the mark’ which is often clumsily translated as sin.

Just two examples: in a prayer called the Ashrei we say: “Hashem is close to all who call out…” and in the Hallel psalms we say “From the narrow place (meitzar) I called out to you, and you answered me from an expanse”.

Part of the Haggadah describes four types of individuals and personality types: The scholarly one, the one who resists learning and being part of Passover, the one who understands things on simple terms, and the one who does not yet know questions to ask. The Seder begins with the asking of questions, making everyone who might not know things feel comfortable.